From the catalog text:

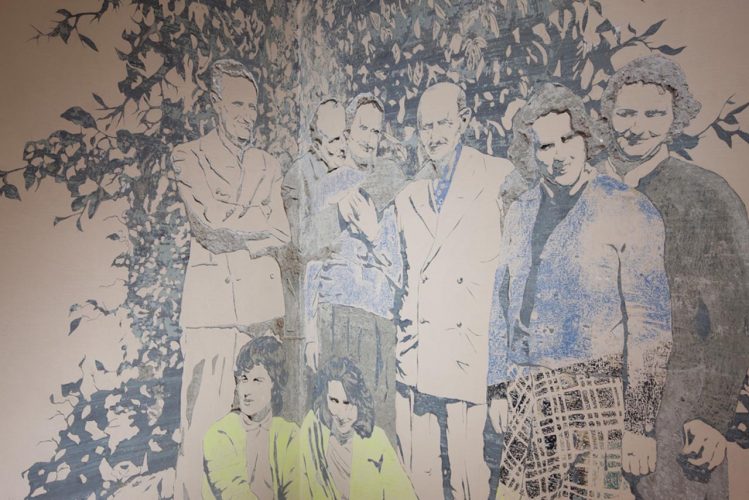

Otto sotto un tetto is the Italian title for the American sitcom Family Matters. The Testori family also had eight members: mother, father, two sons, and four daughters. People used to keep busy back then, in the evenings, when there was no television.

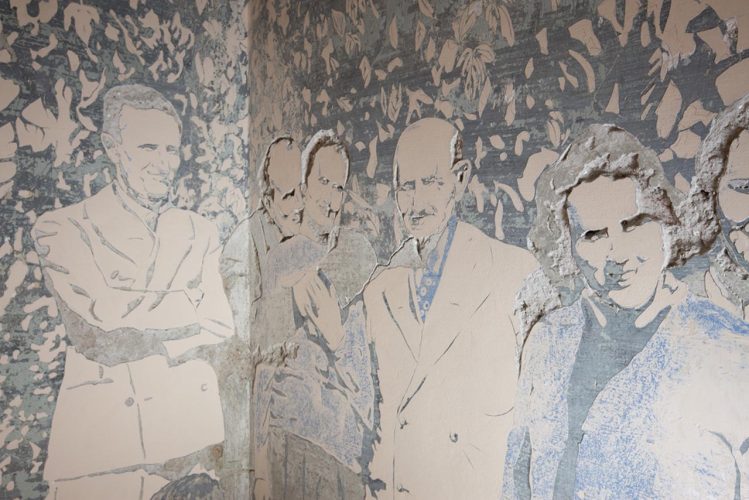

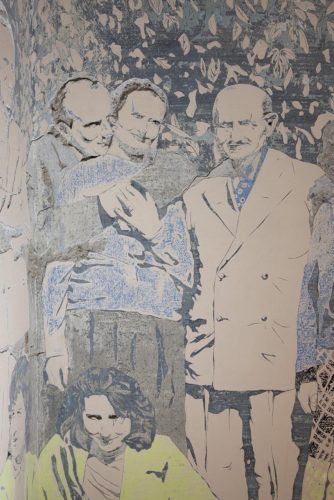

The image depicted is taken from a photo — the only one I found with the whole family together, posed in front of one of the large trees in the villa’s garden.

The work was created by carving directly into the wall, gradually revealing layers of paint, plaster, cement, and brick. It’s a technique I had previously used only once, for Pindemonte in Geneva. I remember it clearly — it was Christmas. I always seem to get new ideas at Christmas; I don’t know why. I was in the bathroom — like Freddie Mercury when he wrote Crazy Little Thing Called Love (except he was in the bathtub, and I was on the toilet) — flipping through a catalog from the CesaC in Cuneo.

Suddenly, I came across a photo of a piece by William Anastasi: a strip of wall chiseled out, with the rubble left right below it, as if a god had passed through and carved the stone with his pinky. Revelatory, I thought.

Right after that, I emailed Barbara, who had been asking for a new idea for the upcoming May exhibition at Analix. That’s when I thought of these figures — these “guardians” carved into the gallery wall — and of their ashes, enclosed in urns below.

I remembered very clearly that dozens of artists had painted those very walls: from Julian Opie to Martin Creed, from Matt Collishaw to Alex Cecchetti, Luca Francesconi, Jessica Diamond, and even myself a couple of times. I thought that slowly, with a box cutter and a lot of patience, it would be possible to uncover all the layers of paint, reconstructing the archaeological history of the gallery simply by exposing all those colors.

Little by little, the idea took shape and became Pindemonte: a kind of joyful danse macabre, where eighteen characters — jumping, playing, having sex — run straight into the arms of death. All their ashes were collected in eighteen urns, like a small cemetery of painting.

I remember that, for the first time in my life, I cried from emotion once the work was completed, after sleepless nights spent scraping dozens of square meters with a box cutter.

And so here too, at Casa Testori, I let the walls do the talking: as if they had been soaked with photosensitive materials, they return to us the features of the people who lived here in the past — presences that still permeate (believe me — from someone who spent nights inside those walls), kindly, all twenty rooms…

Andrea Mastrovito, Family Matter, carved plaster, site-specific dimensions, 2011.