(KEEP THE FIRE BURNING. SURPRISES OF CONTEMPORARY ART)

A project by Casa Testori

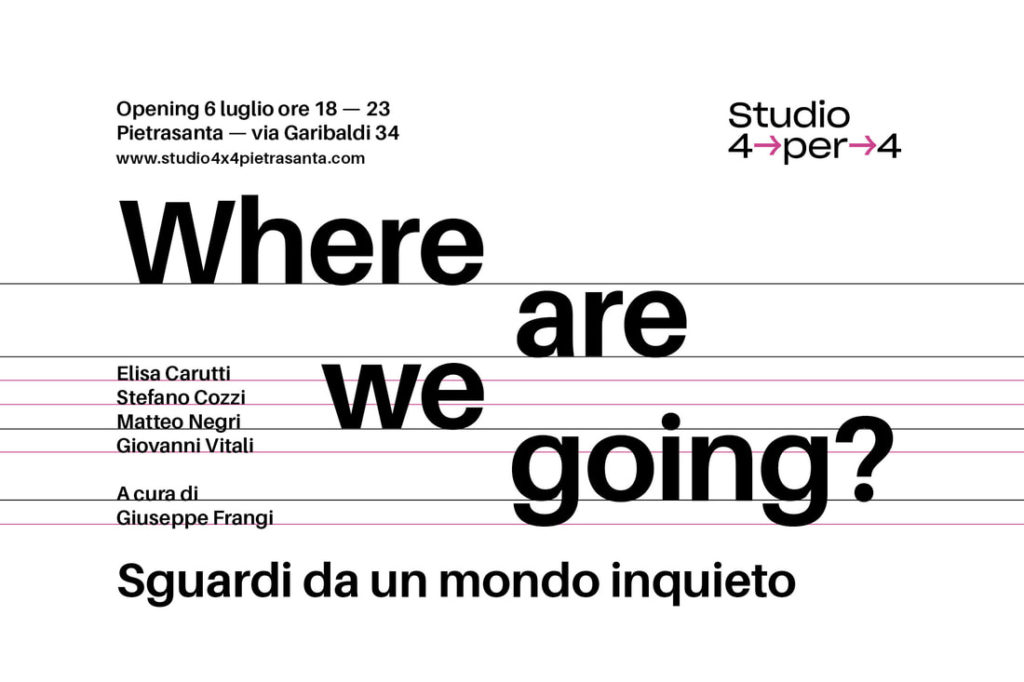

Curated by Davide Dall’Ombra, Luca Fiore, Giuseppe Frangi and Francesca Radaelli

Meeting di Rimini

20-26 August 2015

ONLY ONE TIME: THE PRESENT

Giuseppe Frangi

Let us begin with a statistic: never in the history of man has there been so much artistic production as there has in our own days. Never have there been so many artists, not just in terms of absolute quantity – this would be logical given that there are now seven billion of us on the earth – but also in terms of the percentage of people who have chosen art as their way of life. Why do we want and need art so much? And why should this happen in times like ours, when utilitarian logic always seems to have the upper hand? These are questions that might be answered as Gio Ponti answered them, with a charming anecdote. He imagined that God, at the end of time, received men one by one, and was pleased with the work that he – God – had done and with what he had created. But when, after an innumerable stream of professions, an artist came forward, God was nonplussed. The idea that men might become artists was something he had not foreseen. Instead of being annoyed, though, he was all the more pleased with those of his creatures who had surprised their own creator, by doing something that not even He had bargained for. What does this anecdote suggest? That art is the activity which makes man get outside himself, it is the space of the unexpected, of the unnecessary, of the gratuitous. It is the place where the desire that moves man in every moment of his life struggles to reach an objective form, or to express itself in words.

It has always been like this, from the time of the Lascaux rock carvings till our own days. Just as there is no time without art, neither is there any code that ensures the goodness of this art. In the words of Damien Hirst, one of the phenomena of contemporary art, a person who inspires both scandal and front covers: «Great art is when you understand something you didn’t already understand about what it means to be alive».

One thing that is certain is that art can never be equal to itself, it must always accept the risk of the new, of what has not been said before. Even at the cost of failure, of coming right off the rails of its own nature.

Art has another characteristic: it knows only one time, and that is the present time. This is always true, in the sense that even when we look at a great work of the past, it is not great by decree, it is great because it makes the strings of our present vibrate when we look at it with a gaze that belongs to no other time in history. And the present of art is not only ideal, interior, subjective, it is also objective. The Artist Is Present is the title of an extraordinary performance that excited hundreds and hundreds of visitors to the MoMa of New York in 2010. Marina Abramović, the artist, remained seated throughout at a table, relating by looks only, with the visitors who, one by one, sat down opposite her: 1,565 people for a total of 700 hours of performance. An extremely intense experience, humanly and emotionally, in which the artist, by delivering herself up to the other person’s gaze, in a certain sense “giving” herself, touches something that had to do with both her own destiny and that of the person in front of her.

It is difficult for the artist today to live in the shadows, because the media systems are often an integral part of his or her action. Artists are people who are often called upon to reveal everything about themselves, to render naked their own lives, as did Tracey Emin, an exponent of Young British Art, with a work that had great media impact and was disconcerting to the spectator; none other than her own unmade bed, after her body had “lived” in it for four days, dominated by an instinct for death. When she got out of it, she saw in that form, which related the potential undoing of life, a powerful image, a sculpted form of life itself, of her life. We might well wonder how men of the next century will look at that bed, what they will see in it. But the idea that an artist’s goal is to conquer time is not only somewhat vainglorious, it is also the child of an aca- demic rhetoric that contemporary art is to be thanked for having swept away.

Art is a tool for unplanned relations with men of its own time. It is a language that succeeds in touching deep chords, in unforeseeable ways and times. When Ai Weiwei, from his studio in China, conceived the installation for the now disused prison of Alcatraz, he created a work that proved to be a gesture of reparation, highly poetic and therefore very human. His filling the prison washbasins, bathtubs and even lavatories with delicate flowers in white ceramic had the effect of a homage to everything human that had been profoundly humiliated there. When Ron Mueck, the extraordinarily skillful Australian sculptor, rendered monumental the figures of two elderly bathers, the effect was deeply unsettling because it invested with emotion and passion a situation that was aesthetically unattractive, and because it restored the eternal theme of the body to its central role in the creation of art. This is the theme that the British artist Jenny Saville has obsessively and explosively explored over the years. She has poured masses of astounding physicality onto her canvases. After undergoing the experience of maternity, she succeeded in gathering this energy into the narration of a relationship: that between her body and the bodies of her children.

The body also enters the field, metaphorically, in the powerful installation by Anish Kapoor, an Indian artist naturalized British. In Shooting into the Corner (2008-2009), a cannon fires balls of blood-red wax, a quasi-organic material, into a corner of the room, with implacable rhythm and with mindless, calculated violence. The effect is striking without being in any way theatrical. Another type of violence is offered by Alberto Garutti: a luminous violence, one that dazzles the spectator in order to trigger off a dimension of wonder. The 200 lamps that light every time a thunderbolt falls in Italian territory are an invitation to open a breach in our excessively urbanized, calculating minds.

Damien Hirst, Marina Abramović, Ai Weiwei, Ron Mueck, Jenny Saville, Anish Kapoor and Alberto Garutti are brought together here to offer an alternative view of contemporary art. A view that is curious and open-minded in an attempt not to remain hostage to the usual commonplaces. Today’s art is certainly anomalous in the market values it has attained – to such an extent that one of the greatest and most serious of present-day artists, Gerhard Richter, has publicly declared himself embarrassed by the quotations achieved by his works. Art is also often reduced to an idiotic exercise in nihilism. But in the midst of all this mire – as always in human history – “threads of gold” are to be found that it is a pity not to follow, observe and know.

These “threads of gold” relate an unexpected, sometimes unsettling, sympathy for all that is human. And they relate it in equally unexpected forms, often very different from those to which tradition has accustomed us. But art is not obliged to respect any particular form. Indeed, it is in its very nature to break away from forms, even those of the very recent past, and venture into new terrain. This is its response to the stimuli arriving from the novelties introduced by human life itself. «Art is an open door towards possibilities», in the words of one of today’s major curators, Hans Ulrich Obrist, in his discussion of the artist Leon Golub.

«I have always been interested as an artist in how one can somehow look again for that very first moment of creativity where everything is possible and nothing has actually happened. The vacuum is that moment of time before creation when anything is possible», stated Anish Kapoor in an interview, pressed by numerous questions on his concave and convex forms and on his works in red wax that “create themselves”.

This exhibition aims to follow some of these «threads of gold», not through the works, but by narrating the works, even in the form of a spectacle. The choice is not intended to induce consensus, but to arouse curiosity. It present instances of extreme boldness, which are worth coming to terms with. Boldness of language, or a boldness of approach that leads the artist to penetrate the fibres of reality far more than we can. At times this boldness may be induced by the means available to the artist. This was the case with the great British artist David Hockney; with the arrival of the iPad, he realized he would have to venture into painting on the tablet, that this was a stimulus that would produce surprising results. And indeed, the beauty of his “artificial” images, produced with electronic brushes, testifies to a view that has become more acute, more excitable, which penetrates further into reality. And this is how the artist David Hockney – but we can say the same of all the other artists present here – is still continuing today to amaze God.

THE EXHIBITION

A curious and open look to avoid being hostage to the usual clichés. Today’s art is certainly also a matter of the market, often reduced to a pure exercise in nihilism. But in the midst of this mud – as always in the history of mankind – one can discover golden threads that it is a pity not to follow. They are golden threads that tell of an unexpected, sometimes disconcerting, emotion for the human being. And they tell it in equally unexpected forms, sometimes very different from those to which tradition has accustomed us. But art is not constrained by any form. The exhibition follows some of these “golden threads” through the narrative, even spectacular, of these works. The spectator was greeted by a video that introduced, not without irony, the theme of today’s art, outlining some of the characteristics that differentiate it from that of past centuries.

Go to the bookshop